METAIRIE, La. — He told her to get on her knees and count to 10. And that’s what Sara Cusimano did. She closed her eyes and counted. “One,two,three…”

She thought her attacker would run away while she counted, but instead he put the gun between her eyes and pulled the trigger.

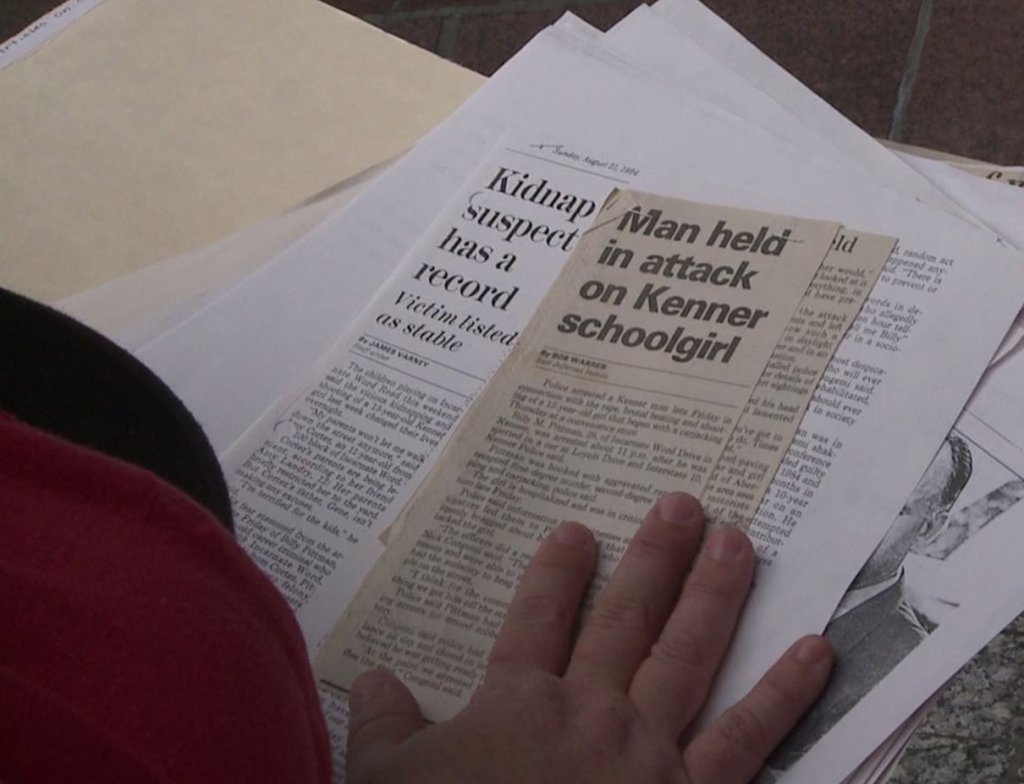

It was one of the biggest news stories of the year. In 1994, when Sara was 13 years old, she was kidnapped as she sat in her mom’s car next to the gas pumps at a Time Saver Convenience Store in Kenner. Her mother had gone inside the store to pay for the gas.

She had just finished her first day of classes as an eighth-grader at Dominican High School. She was wearing her school uniform, listening to the radio. And then she was trapped with a stranger in a speeding car.

Across the area, police scanners crackled with the report: armed man, kidnapped girl, stolen SUV heading west on I-10. Reporters from all the New Orleans TV stations scrambled to follow the chase. Current NBC anchorwoman Hoda Kotb was one of the reporters, working the night shift for WWL-TV. I was working the same shift for WDSU.

Who would get to the crime scene first? Who would get the best interviews with witnesses at the gas station, or with family members who were huddled with Kenner Police detectives? Before the 10pm news that night, when we found out what had happened, I didn’t feel like a competitive reporter with the lead story. The story was so awful I felt sick.

In the evening rush hour traffic, Kenner Police lost sight of the SUV. The kidnapper, a drifter with a criminal record named Billy Pittman, kept his gun pointed at Sara while he drove- and she cried. One of the tires had a flat, and Pittman pulled off the interstate and into a deserted area near the airport. Then he led Sara into an overgrown field, while she begged him to let her go.

She says she tried to fight him off, but he held the gun to her head while he raped her. Then he told her to get on her knees and start counting. Before she got to “four” the bullet pierced her forehead and came out of her skull behind her right ear.

“I remember what it felt like,” Sara says in a new book about gun shot survivors. “I remember my body flying backward and slamming into the ground.”

A Kenner Police officer found her lying in the field, bleeding profusely. She was incoherent, and the officer called for an ambulance. The ordeal was over in a couple of hours. But not for Sara.

Today, she talks easily about her recovery: the temporary paralysis, the multiple surgeries, the damage to her hearing, and worst of all, the PTSD.

But when I interviewed Sara at Children’s Hospital in New Orleans a few months after the shooting, she was just a teenager who didn’t want to be known as “that girl.” She said very little and seemed relieved when the interview was over.

“I wanted to ignore it, I wanted life to go back to the way it was,” she says. “I didn’t want people to treat me differently, and there’s kind of no getting around it. Life is different. And it’s okay to accept that and go from there.”

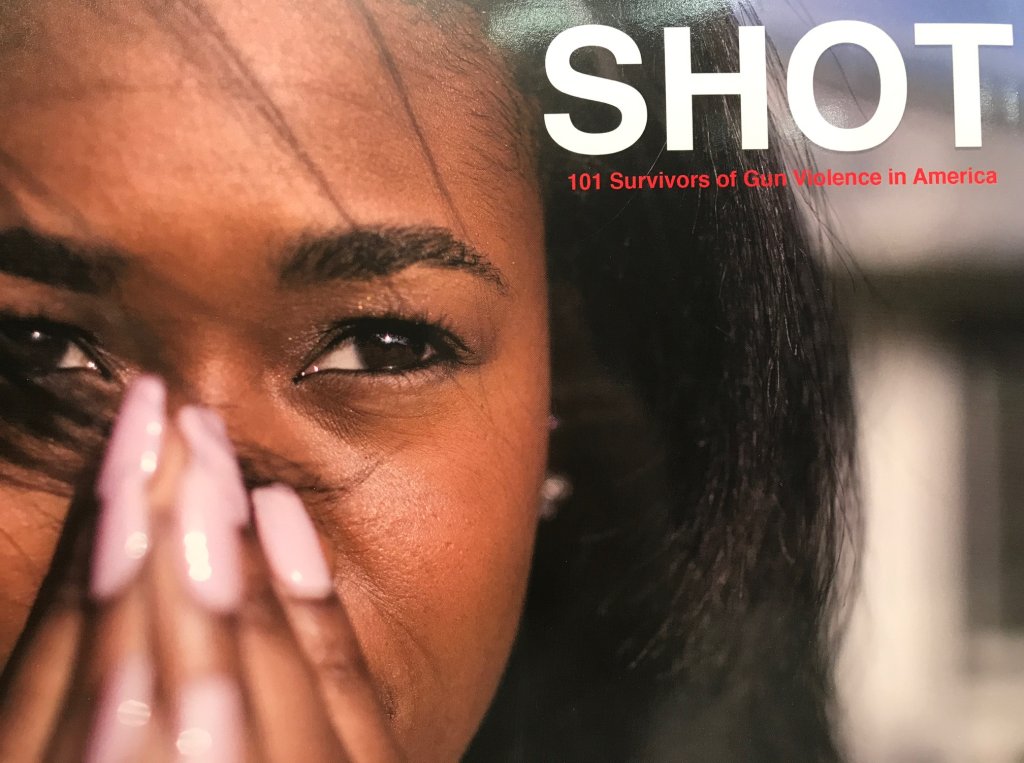

Part of that acceptance, was agreeing to share her story in the new book called “Shot.”

The book is a compilation of photographs of 101 shooting survivors from across the country.

In the book’s preface, photographer and author Kathy Schorr writes that her motivation to tell survivors’ stories began with her own “encounter with a gun during a home invasion.” Later, she says she realized that people killed by gunfire often “become ‘folk’ heroes in neighborhoods decimated by shootings.”

Schorr writes that she wanted her book to be “focused on the others – the survivors of gun violence. Where were their tributes? Who thought of their trauma?”

For Sara, that trauma has never gone away. The scar on her forehead is barely visible — just a thin, pale line between her eyebrows, mostly hidden by her bangs. But physically and emotionally she says she’s still damaged by the shooting. When Schorr asked her to be one of the survivors featured in “Shot,” she hesitated. In the end, Sara agreed to let Schorr take her photograph in the place where she was attacked, the deserted lot that she had not gone near since the shooting.

It was “one of those things that you think you’d never be able to handle,” she says. “You would just kind of collapse and not do it. And you do it, and you realize that you’re okay… You put one of those demons to rest.”

Another way Sara has been trying to “go full circle” in her recovery is by reaching out to people who were part of the story the night she was shot. When she sent me an email a few weeks ago to tell me about the new book, it was the first time I had heard from her since the shooting 23 years ago.

“Gun violence remains such an unfortunate part of New Orleans, ” she wrote in the email, “that sometimes people really just need to see the true picture of what gun violence leaves behind.”

Of the 101 shooting survivors profiled in “Shot,” at least one — also from the New Orleans area — died before the book was published.

Deborah Cotton, a music reporter and blogger, was hit by a stray bullet during a shooting at a second line in the 7th Ward on Mother’s Day in 2013. Cotton initially recovered, but after multiple surgeries she died this year– almost four years to the day that she and 19 other people were shot in a gun fight between rival gangs.

Kathy Schorr says she hopes her book “will act as a catalyst for people to address the life and death issues of gun violence.” But she emphasizes that she’s hoping for “dialogue,” not confrontation, pointing out in the book’s preface that some of the book’s survivors are gun owners themselves, and one was a member of the National Rifle Association.

Sara Cusimano has become a member of the Louisiana chapter of “Moms Demand Action for Gun Sense in America,” advocating for gun regulations and survivors’ rights. She met parents of children killed in the Sandy Hook school shooting in 2012, and she recently wrote an editorial in The New York Daily News about the shooting of U.S. House Majority Whip Steve Scalise, the congressman from Metairie who remains in serious condition at a Washington hospital.

“I know firsthand the journey he and the other survivors will face long after the news cameras go away everyone else moves on,” she writes. “This time we must transform our anger and grief into action that will change the course of our nation’s dialogue on gun violence for good.”