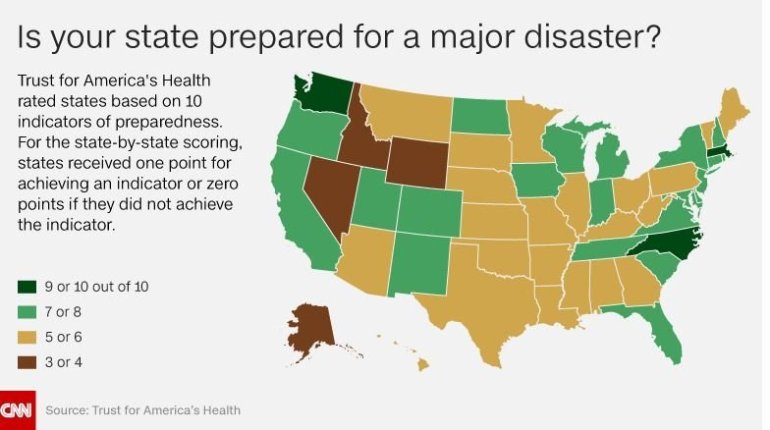

(CNN) — On average, one new contagious disease has emerged each year for the past 30 years. Yet most states are easily caught off guard, according to a new report from Trust for America’s Health, issued Tuesday. Twenty-six states and the District of Columbia scored a six or lower on 10 key indicators of public health preparedness, according to “Ready or Not? Protecting the Public from Diseases, Disasters and Bioterrorism.”

(CNN) — On average, one new contagious disease has emerged each year for the past 30 years. Yet most states are easily caught off guard, according to a new report from Trust for America’s Health, issued Tuesday. Twenty-six states and the District of Columbia scored a six or lower on 10 key indicators of public health preparedness, according to “Ready or Not? Protecting the Public from Diseases, Disasters and Bioterrorism.”

The worst offenders were Alaska and Idaho, each scoring 3 out of 10. On the flip side, Massachusetts scored the highest at 10 out of 10, trailed by North Carolina and Washington state, each scoring 9s.

“There are differences in how states should be prepared, but there are some baseline abilities that all states should be able to achieve,” said Laura Segal, a co-author of the report and director of public affairs at Trust for America’s Health, a nonprofit with no financial ties to industry or government. The organization is funded by foundations, including the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.

The report’s authors grade California, Connecticut, Iowa, New Jersey, Tennessee and Virginia at 8, while Colorado, Delaware, Florida, Indiana, Maryland, Michigan, New Hampshire, New Mexico, New York, North Dakota, Oregon, Rhode Island, South Carolina, Utah and Wisconsin all earned scores of 7.

Arizona, Arkansas, the District of Columbia, Georgia, Hawaii, Illinois, Kansas, Kentucky, Louisiana, Maine, Minnesota, Mississippi, Montana, Nebraska, Ohio, Pennsylvania, Texas and Vermont received 6 out of 10 points, while Alabama, Missouri, Oklahoma, South Dakota and West Virginia merited a score of 5 out of 10. Finally, Nevada and Wyoming each received a grade of 4.

Dwindling resources

Compared with last fiscal year, more than half (26) of the states either increased or maintained funding designated for public health for the current fiscal year. Though this is an accomplishment, it’s not enough, Segal and her co-authors suggest. Often, after an emergency ends, state and local governments cut back on spending earmarked for disaster, as happened after Hurricane Katrina.

However, the 2008 recession took a substantial bite out of funds allocated for health emergencies. Nationwide, hospital emergency preparedness funds decreased from $515 million in 2004 to $255 million in 2016, estimate the authors.

Dwindling resources may explain why just 10 states vaccinated at least half of their population against the seasonal flu during the 2015-16 flu season. Similarly, only 10 states have a formal program either in place or in progress for getting private-sector medical staff and supplies into restricted areas during a disaster.

On the positive side, 45 states and the District of Columbia increased testing speeds for detecting foodborne outbreaks, while 32 states and DC received a grade of C or higher on state-level preparedness for climate change-related threats. The report also sees improvements in the areas of emergency operations, communication and coordination and support for the Strategic National Stockpile of medical supplies and the ability to distribute medicines and vaccines during crises.

Additionally, major upgrades have occurred in public health labs, and liability protections during emergencies have become more sophisticated.

Still, there are major weaknesses across the nation.

Pandemics and bio-error

The most striking are gaps in the ability of the health care system to care for a mass influx of patients during a major outbreak or attack and lack of a coordinated biosurveillance system.

“Biosurveillance does remain a major ongoing gap,” Segal said. Given all the recent technological advances, there is the potential for a “near real-time” surveillance system to detect outbreaks and to track containment effort, yet the dream eludes our government, she said.

“Some of the big challenges of course are, there are legacy systems that have been in place for a long time, many of them that track different things with little integration,” Segal explained. “And there has not been funding to really upgrade the infrastructure and technology.”

Chris P. Currie, director of emergency management national preparedness at the US Government Accountability Office, sees some improvements since his own office issued a 2013 report about the nation’s biodefense capabilities, but overall, those capabilities are in sad shape. A number of departments lack up-to-date policies and procedures, he said.

Dangerous viruses and other biological agents require more oversight, said Currie, recalling a recent incident in which scientists accidentally shipped live viruses to the wrong lab, presenting a danger to the public.

“We’ve done a lot of work in the last decade on just the coordination of biodefense at the federal level,” Currie said, adding that the key theme is, “there is no real one accountable position or entity within the federal government for overall biodefense.”

Instead, “the alphabet soup of federal departments” is responsible, and no one entity has direct oversight over all.

“In 2011, we reported that there were more than two dozen presidentially appointed individuals with biodefense responsibilities,” said Currie, with multiple federal agencies assuming some sort of responsibility.

This makes it extremely difficult to try to prioritize not just actions but funding across the federal government to address areas of greatest risk to the public, he added.

In short, there’s no overarching strategic approach. Segal sees similar problems when it comes to caring for an influx of patients during a mass event.

Global disruption

“It is considered to be a shared responsibility,” Segal said, with federal funding to support state activities, often additional federal emergency funds and shared responsibility with the health care sector. This includes how insurers pay for care and coverage and how public funds can support private providers.

“There have been lots of different expert groups and meetings that have helped advance some of these issues,” she said, but overall, these capabilities could be better addressed and integrated across the different stakeholders.

Though infectious diseases routinely cost the country a minimum of $170 billion year, a severe new flu pandemic could run more than $680 billion — about 5.5% of the Gross Domestic Product, according to the report.

With the potential to disrupt the global economy, Segal and her colleagues recommend that regions, states and communities across the nation develop strong, consistent baseline public health abilities. They also call for consistency and coordination of planning along with stable funding.

A stronger US food safety system, they note, would decrease our nation’s vulnerability to health emergencies. They also recommend programs to address antibiotic resistance, vaccinations and climate change.

“A strategic modern biodefense also yields strong returns,” conclude the authors. “Investing in prevention and effective standing response capabilities helps avoid the costs in dollars and lives.”